Arthur Roy Mitchell

1889-1977

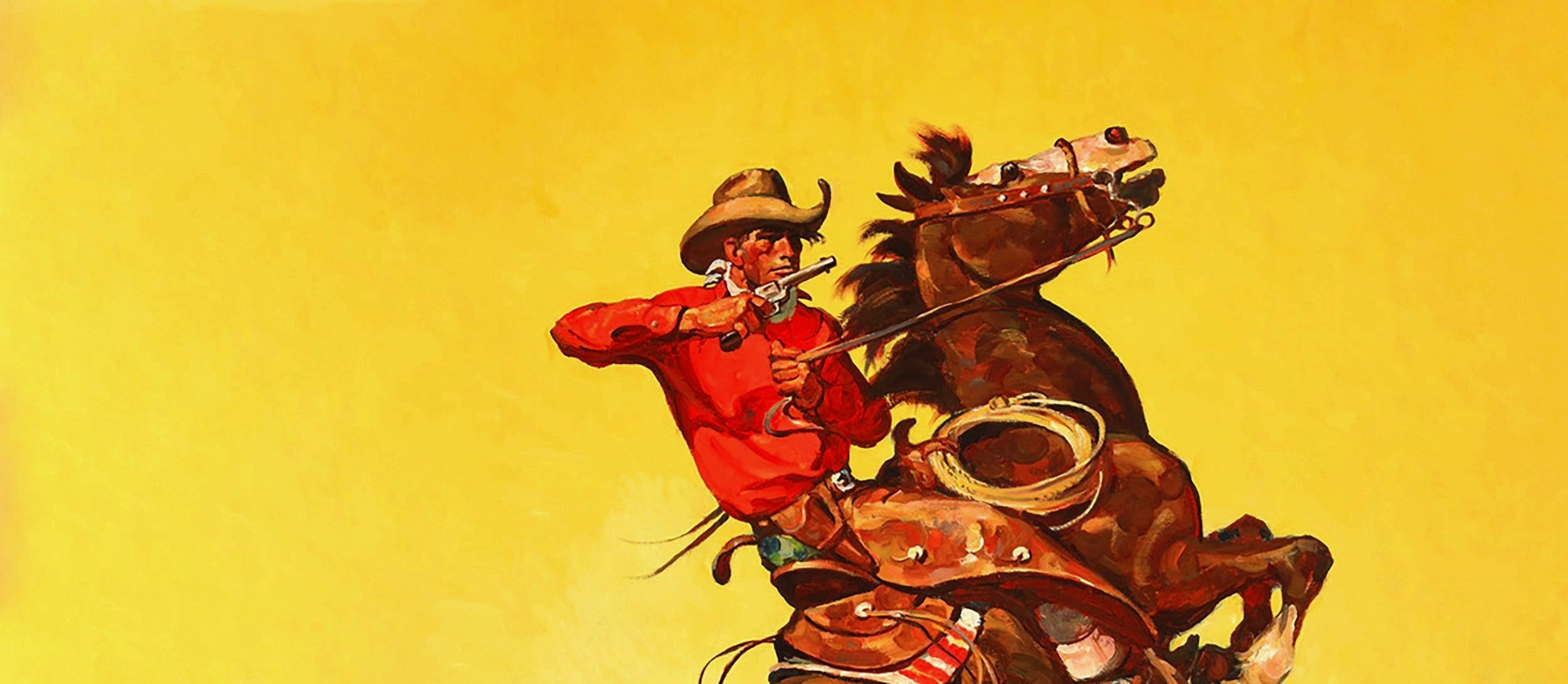

Mitchell painted cowboys— real, working cowboys—

Alongside cowgirls atop bucking broncos, two-gun pistol packing rustlers, and the vast landscapes of the American West. Mitchell was a prolific artist, his career began in his youth with sketches of Western life and carried him across the country— leaving a bright brand on the art world and cementing a vivid, dynamic image of the American cowboy in its imaginary.

The Early Years

Arthur Roy Mitchell was born on December 18, 1889— In an adobe house on his parent’s homestead just west of Trinidad, Colorado, under the southwestern mesas of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. After some time, the family moved to town and Mitchell grew to young adulthood just four blocks from the Old Santa Fe Trail, which had been outmoded by the railroad but a few years before.

His adolescence was marked with a dilemma: he wanted to be a cowboy, but found himself sketching all that surrounded him with a furious determination. At age seventeen, he began to work for the famous A6 Outfit of the Adams Cattle Company in Vermejo Park, New Mexico 40 miles south of Trinidad. He wrestled bawling calves to the ground for branding during Spring and Fall roundups, finding time for quick drawings of horses straining, cattle balking, and men sprawling after being bucked off their horses. Among his personal papers was a carefully drawn portrait of Thad Porter, the A6 ranch foreman. Between roundups, he hired out to neighbors and ranching friends as a general ranch hand. As he matured, he weaned himself away from his cowboy dream, but never forgot it.

In 1912, Mitchell became the advertising and circulation manager for Trinidad’s own Chronicle News, after getting his start illustrating their cartoons.

By 1913, Mitchell said he had had grown restless. He needed something more, so he took a job with an advertising agency in Boise, Idaho, once again working as a cartoonist. He remained in Idaho for several years, all the while taking art and drawing classes whenever and wherever he could. In 1917, in the midst of the first World War, Mitchell joined the army and was stationed at Camp Lewis in Washington state, given the rank of Drill Sergeant and passing on to officer’s training by 1918. After the conclusion of the war, Mitchell accepted a position at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. At this point, he had spent more than a decade in the Pacific Northwest— pursuing each and every opportunity to expand his studies in the arts and incubating his developing style with significant influence from painter C.M. Russell.

While working for the papers, Mitchell familiarized himself with, and even sold, some of the advertising art by the California-based artist Harold von Schmidt. The two painters soon became friends, and— upon hearing that von Schmidt was leaving to study at the Grand Central School of Art in New York with teacher Harvey Dunn— Mitchell decided he would do the same.

Mitchell Moves to New York to Study at the Grand Central School of Art

In the fall of 1925 Mitchell sold all everything of value to his name and took a train bound for New York City where he enrolled in the Grand Central School of Art, located on the top floor of Grand Central Station.

There, he studied under artist and teacher Harvey Dunn— arriving smack in the middle of Prohibition, and it’s associated speakeasies, flappers and outrageous lifestyles. The city’s dense population, busy streets and packed skyline was a far cry from the small, Western, mountain town he hailed from.

Harvey Dunn was a demanding teacher, and he knew he had two Westerners in his class— Men like himself, who had lived in the West, obviously loved the West, and lived as cowboys. Dunn, Mitchell and von Schmidt formed an immediate kinship and became lifelong friends.

Over the course of many summers, Mitchell would come home to Trinidad to paint. He would stay at his sister's ranch and often invited Dunn and von Schmidt to come along on trips throughout Colorado and the Southwest.

Mitchell studied at the Grand Central School of Art with Dunn until 1927 when Dunn moved his classes to his personal studio in New Jersey. Mitchell immediately moved out of Manhattan and into a remodeled barn and studio in Leonia, New Jersey just down the street from Dunn, where he would live and paint for many years.

GRAND CENTRAL SCHOOL OF ART, ARCHIVAL COLLECTION.

MITCHELL REIGNS OVER WESTERN PULP.

Harvey Dunn once gave a word of advice to A. R. Mitchell, "When they ask you what a picture is for," he said , "tell them, 'for sale!'"

In January of 1927, Mitchell sold several paintings for the covers of pulp magazines Cowboy Stories magazine and Northwest Stories. Mitchell's intimate knowledge of genuine cowboys and familiarity with horses, along with his now finely-honed skills, allowed him to find work creating western pulp covers at a time when many other artists were struggling to find work.

He found success painting such cover art for myriad Western novels and weekly magazines from the 1920s through the 1940s. Receiving acclaim for his remarkably accurate details of Western gear, colorful action scenes, as well as his superior anatomy of the horse— it was not uncommon for Mitchell to have multiple covers on view at newsstands all over the country.

By the latter part of the 1930s, Mitchell had begun to paint full composition paintings with backgrounds, foregrounds, skies and well placed figures. In 1935, Mitchell began working in the field of book jacket art. Mitchell established a relationship with the Houghton Mifflin Company, a book publisher based in Boston, and created book covers for The Spur of Time, The Spider Web Trail and The End of Black Jack, a story about the notorious train robber and bandit, Thomas (Black Jack) Ketchum.

MITCHELL’S LANDSCAPES

Mitchell painted landscapes throughout his lifetime, though many in our collection do not have a date attributed to them. Some were painted during his summer trips back to the West, en plein air , during his journeys spanning the 1920s through 1940s— and some were painted after he moved back permanently to Trinidad in 1944. Adobes, horses and cattle are often depicted and the locations are as varied as the Western landscape of mountains, mesas and high deserts that make up the West and Southwest. There is a rich tradition of landscape painting in the American West, and Mitchell cemented his place with his use of color in both subtle and dramatic hues— reflecting the notion that this cowboy wore two hats, one of an illustrator and another of a fine artist.

By the start of World War II, Mitchell— tired of the crowded East Coast and the stubborn new editors of the pulps— decided to shut down his painting career in the East and return home to Trinidad to help raise cattle on his sister Tot's ranch. Around this time, he received grim news, a cancer diagnosis, and feared he may not have much time left. He produced many paintings during his three years on the ranch, many of which are of the beautiful Stonewall Gap area of southern Colorado, where the ranch was located.

The Return to Trinidad

In 1944, the president of Trinidad State Junior College offered Mitchell a two year teaching position, which he retained until 1958. As the war drew to a close, Tot and her husband decided to sell their ranch and move to Denver, where Mitchell would join them decades later. But for the time being, he remained in Trinidad, working to preserve the legacy of the West he loved and keep its vision alive for the coming generations. An icon in composition and pedagogy alike, several of Mitchell's students went on to become successful artists, photographers and teachers.

Thomas Barnett, who went on to study art in Paris, said of Mitchell, "He was elite in the Jefferson vein. He loved the Southwestern landscape and the Western culture. He loved art, and he loved to paint; this is what he taught. He taught me to love art, to paint, and to appreciate the Western culture, the adobe, the Indian, and the cowboy."

Mitchell, Historian and Preservationist.

Mitchell's love of history led him to yet another role —a local historian and advocate for preservation.

In 1955, he heard that the first house built in Trinidad, the adobe Baca house, was for sale. It was facing demolition, with plans to turn this regional relic into, of all things, a gas station. So, Mitchell jumped into action. He wrote "If it is possible for a house filled with history and nostalgia to get right in the middle of an old man's life and cause him to do things he ought not to do, that is the case with the Baca house."

Mitchell and several friends quickly purchased the building and he petitioned the City to grant it protective status and create a museum. The City agreed, but only if Mitchell would join the project as a curator. Mitchell also donated a large collection of Western memorabilia, personal photographs of the Southwest from 1910 on, historical guns he had used as props for his paintings, and historical documents he had collected over the years. Already on a curatorial path, Mitchell became instrumental in the development of the Bloom Mansion into the current Trinidad History Museum— He remained a s curator and historian for the Trinidad Historic District until 1975, just two years before his death.

An Enduring Legacy

In 1975, at the age of 86, Mitchell moved to Denver to be close to his sister— where he died two years later on November 15, 1977. Mitchell's sister, Ethel "Tot" Erickson, laid the groundwork for opening the museum in his honor, completing the task only a year before her own passing.

Mitchell once reflected on his years accordingly: "You look back over the trail, and you see the fine friends you've made, and you see you've managed to make a living doing something you really loved; so how could anyone ask for more?”

Awards, Honors, and Collections.

In 1973, the National Academy of Western Art (NAWA) was organized to showcase work in the tradition of artists such as Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington. Arthur Mitchell was one of the original inductees.

In 1973, Mitchell was inducted into the National Academy of Western Art at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In 1972, Mitchell was named an honorary member of Cowboy Artists of America.

Founded in 1965, in Sedona, Arizona by artists Joe Beeler, Charlie Dye, John Hampton and George Phippen, the Cowboy Artists of America had a mission—

To perpetuate the memory and culture of the Old West as typified by the late Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and others; to insure authentic representations of the life of the West, as it was and is; to maintain standards of quality in contemporary Western art; to help guide collectors of Western art; to give mutual assistance in protection of artists’ rights; to conduct a trail ride and camp-out in some locality of special interest once a year; and to hold an annual joint exhibition of the works of active members.

In 1974, Mitchell received the Honorary Trustees Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame

In Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Mitchell was lauded as "the man who has done the most for Southwest history" through his paintings. The museum is now called the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum to reflect its mission to: Preserve and interpret the evolving history and cultures of the American West for the education and enrichment of its diverse audiences of adults and children.

Bill and Dorothy Harmsen, owners of the Jolly Rancher candy company, spent 30 years driving a bus across the American West collecting and purchasing western art, amassing a 3,500-piece collection of paintings, Navajo rugs, baskets, jewelry, ceramics and sculptures. In 2001, the Harmsens donated more than 3,000 artworks and artifacts, including paintings, textiles and sculpture, to the Denver Art Museum, where Dorothy Harmsen once served as a board member. The donation led just months later to the establishment of the Denver Art Museum’s Institute of Western American Art. In the Denver Art Museum's publication, Western Passages: How Candy Built a Colorado Treasure, they note how the Harmsens met with Mitchell in a Trinidad bar and purchased several paintings as well as a Navajo rug. Mitchell, known for not willingly selling his art work, stormed out of the bar but later returned and agreed to their offers. Mitchell, the lifelong bachelor, called his paintings "my children" and rarely sold paintings but did give a few to friends and co-workers when he saw fit.

The Harmsen Collection at the Denver Art Museum